By Donovan Roebert.

The photographic record of the life of Mylapore Gauri Ammal, at least that part of it accessible in the public domain, yields no items depicting her in her youth. Even her performance at the Madras Music Academy presentation on 3 January 1932, when she was forty years old, seems to have gone pictorially unrecorded, although other devadasi dancers who performed at MMA events in the 1930s usually have at least one photograph to document their appearance.

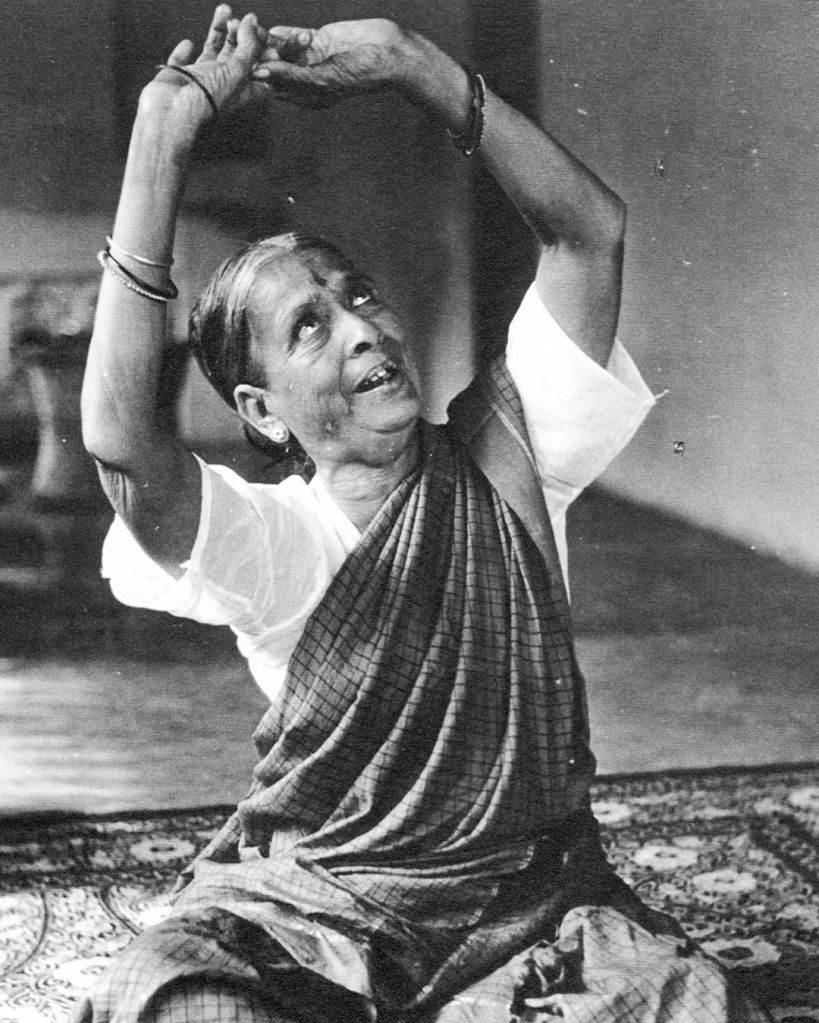

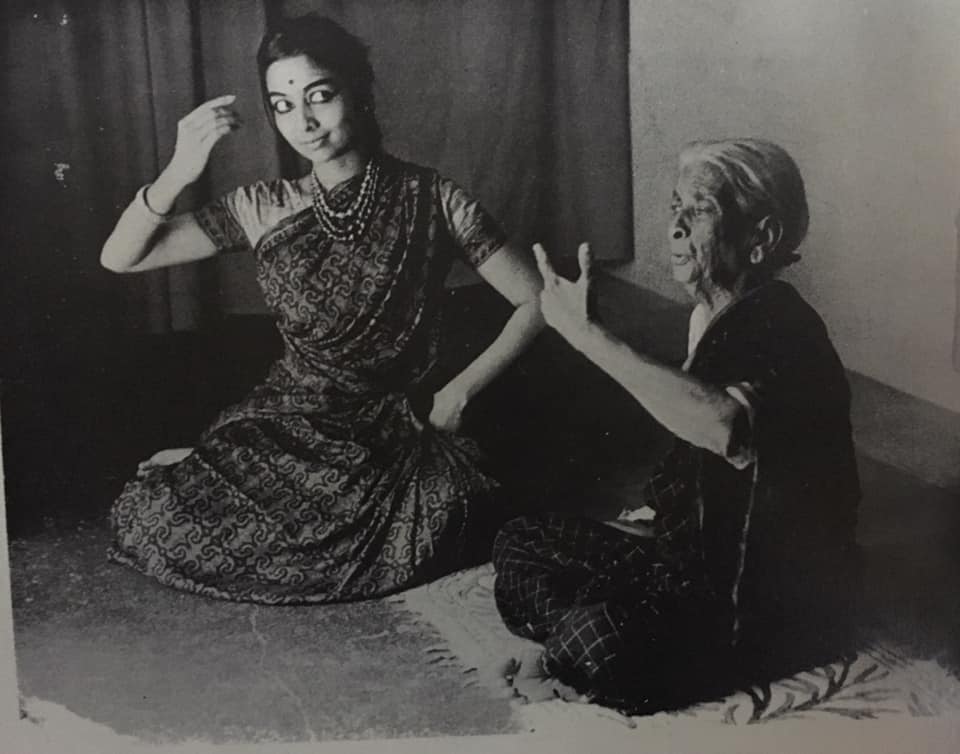

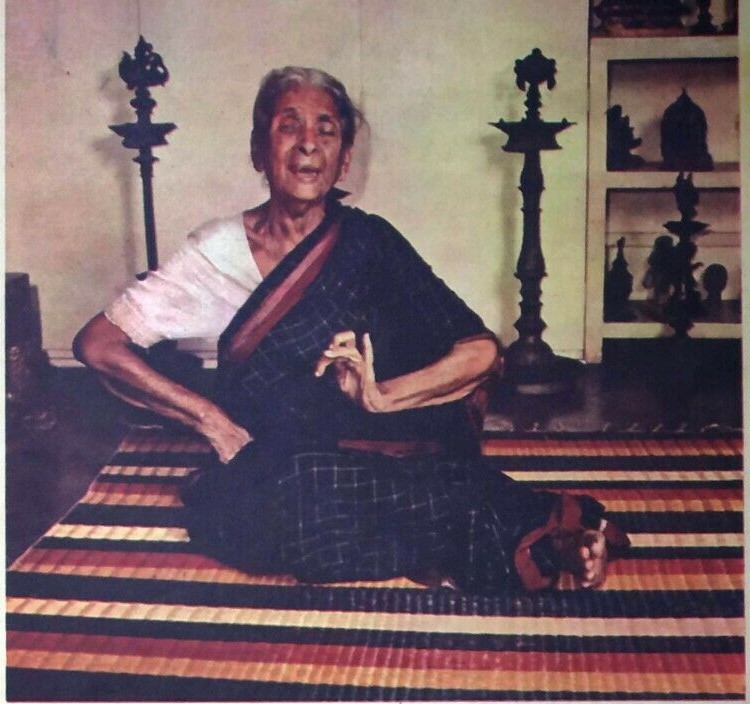

What we have is a set of photographs, always undated, that show her in middle-, old-, and advanced old-age, during the period of her later life when she taught at Kalakshetra and was engaged to teach a number of budding dancers in their private homes. Almost in every case, the pictures are intended to demonstrate her great prowess at the art of abhinaya. These photographs, too, as I have come across them in online searches over a period of some two years, are for the most part inadequately documented as to original sources, and in some cases no sources are mentioned at all.

Gauri Ammal is chiefly remembered as the last serving devadasi of the Kapaleeshwarar Temple in Mylapore, as the dancer who inspired and first taught Rukmini Devi, and as the greatest teacher of abhinaya of her generation. She was the daughter of another great abhinaya exponent, Doraikannammal, who was famed for her great prowess and beauty in her day. According to B.M Sundaram, Doraikannammal was the daughter of the Kapaleeshwarar devadasi Mylapore Dhanammal. Her father was A.K. Ramachandran, who founded the R.R. Sabha.

She was therefore part of an echelon of devadasi practitioners who had gained eminence in the Tanjore tradition, and of which the extended family of Veena Dhanammal, to which Gauri Ammal was closely attached, represents the most preeminent group. T. Balasaraswati studied intensively under Gauri Ammal and is said to have wanted to imitate her technique in all things, sometimes to the exasperation of her other teachers.

In the rising tide of anti-devadasi sentiment, agitation, and the beginnings of legal criminalization of the system, Gauri was evicted from the house on Kutchery Lane put at her disposal by the temple. It is recorded that she found another house from which the gopura could be seen so that she could perform gopuram darshan in the evening at her bedroom window.

So far as I am aware there is no detailed account of her early life, and accounts of her later years are made up of a number of reminiscent eulogies that emphasize the tragedy of her case. She was taught by Nallur Muniswami Pillai and no doubt by her mother too, and the retrospective praises accorded her as a dancer regularly speak of her as ‘renowned’ and ‘unrivalled’. She is said to have had guidance in abhinaya from Chinnaya Naidu and in music from Ariyakudi Ramanuja Ayangar. She was thus a replete repository of the highest gifts that the Tanjore tradition had bequeathed to her generation.

In the case of the standard brief biological outlines, of which there are many repetitive examples to be found, she first comes to public notice through her 1932 performance for the Madras Music Academy. It was this performance which was attended by Rukmini Devi, and which inspired her to take up dance, to engage Gauri Ammal as her first teacher – to the dismay of Dr Muthulakshmi Reddi -, and later to employ her as the abhinaya expert at the foundling school of Kalakshetra. It must be the case, though, that during this same period Balasaraswati was also being taught by her.

Rukmini Devi herself remembered Gauri Ammal, as a teacher and a dancer, in these terms:

‘To a certain extent, all her pupils have benefited from her. Yet there was something they did not capture. A particular posture of the body, a dignity of movement combined with grace and expressiveness of face which had an element of surprise all the time. These were some of the special features of her dance. Perhaps this comes from someone who has inherited by birth the quality which others are not able to have.’

The Carnatic musician, S. Rajam, in an undated interview with Sruti Magazine, had lessons from her in 1929, when he was ten years old, and recalled seeing her dancing at the temple:

‘I had the good fortune of seeing Gauri dance for the Lord’s aradhana every day. Her dance costume was quite simple – pyjamas and an uttareeyam, ankle-bells and minimal jewellery. Her punnagai or smile was more bewitching than any nagai or jewels. It was a treat to watch her. Hands held just so, torso erect, she looked like a beautiful bronze icon. With her hands on her waist, she would begin to dance by taking lilting steps forwards and backwards. The musicians accompanying her would also move along behind her. Her entourage comprised the nattuvanar who also sang, a mridanga vidwan with his instrument tied to his waist, a flute player, Balu the clarionet player, and two or three persons playing the kai talam. Gauri would not perform without Balu and his E-clarionet …’

He also elaborated on the details of her temple service, recalling that she had to be present ‘during some of the rituals along with the archaka, the oduvar and the nagaswara vidwan. Shodasopachara or sixteen different offerings to the Lord as part of the pooja rituals included music and dance.’

As regards the private tuition she gave outside of Kalakshetra, S. Rajam says that ‘as she was attached to the temple, she could not go wherever she pleased. She would only visit homes where she was treated with respect. In most cases, arrangements were made for her commuting to the student’s house. I was probably the only one who went to her house to learn …’

And, about the house itself:

‘Gowri Amma’s house had a central hall or koodam with many pillars and a mutram open to the sky. A gentle breeze blew through the open courtyard. Condiments were often laid out to dry in the sun … My music lessons took place amidst these odours.’

He also gives a sense of Gauri Ammal’s relations with the Dhanammal family:

‘Among those living in the house were Sarasa, a dancer related to Gowri Amma, and Dhanammal’s son Venkatesan who played the harmonium. T. Balasaraswati, mother Jayamma, brothers Viswanathan and little Ranga lived with Gowri for a brief period. The families had strong ties and helped each other in times of need.’

He recounts his impressions of being taught by her:

‘The image of Gowri Amma singing, moving her hands gracefully as she showed the abhinaya for the line, is etched clearly in my mind. She was famous for her abhinaya but I was enthralled by her music. She sang with exquisite voice modulation, highlighting the sirisu and perisu according to the sahitya bhava and raga bhava.’

There exists an interesting video clip of around 2-3 minutes duration in which Gauri Ammal is seen performing. Although the clip is without sound, it still conveys a potent sense of the delicacy and nuance of her abhinaya technique. It is found in the Asia Society archives (24 June 2010) and occurs in an interview with Douglas Knight discussing his book Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life.

Other students also remember the keen effects of her training, among them Sudharani Raghupathy:

‘I had the good fortune to meet and develop further the art of abhinaya from doyennes such as Mylapore Gauri Ammal and Balasaraswati. I soon found that learning under them was anything but formal. After commencing with the primary piece, be it Aasai Mukham Marandu Poche or Velavare, Gauri Ammal would launch into an hour-long elucidation of the same kirtanam or padam. I would watch astounded as her creativity took flight and she embarked on these fascinating descriptions.’

And Hema Malini:

‘During the period Guru Ramaiah Pillai was teaching me, my parents wanted me to also learn from Mylapore Gowri Ammal . This was before I learnt padams from Bala. I had the opportunity of meeting Gowri Ammal through my first Guru, Kandappa Pillai, who introduced Kalanidhi and her parents to us. It’s through her parents that I came to learn from her. She used to come to our house to teach me. I had the privilege of learning some padams from her. She could hardly see in those days as she had cataracts in her eyes. She would sing and do the padams and I would watch her. (Balasaraswati style was very much like hers). Because of her vision she presumed I had understood the padams, and when I nodded she would go to the next. She taught me 5 -6 padams … I can’t remember now why we discontinued – probably her eyesight or travel inconveniences…’

The passage is found at Hema Malini’s now defunct website, and is accompanied by the following very hazy photograph:

It is clear at any rate that Gauri Ammal was a sought-after teacher, and her students included dancers from both the hereditary and the non-hereditary sides of the spectrum as they were in those years beginning to unfold. Among many other non-hereditary dancers who were later to make flourishing careers, she taught Kalanidhi Narayanan, V.P Dhananjayan, Padma Subrahmanyam, and Yamini Krishnamurthy.

It is in any case a fact that most dance students who passed through Kalakshetra had lessons in abhinaya from her. Mayadhar Raut, one of the recreators of Odissi, who trained at Kalakshetra from 1955 to 1959, remembered that ‘in the second year, after finishing the fundamentals, Gauri Amma would take abhinaya classes. Her granddaughter would bring her from Mylapore and drop her at the Central Cottage (biggest classroom) at 1.30 p.m. Everybody used to call her Pattiamma. She would sit and teach padams with expressions and mudras on Telugu poems … She was old and after class would put her head on the tattkali and sleep on a mat on the floor …’

It is clear, then, that even in her later years she went on working hard both at Kalakshetra and for her private students. And it was during this period – the late 1950s – that she began receiving official recognition for her labours and her exquisite capabilities as dancer and teacher. In 1956 she was honoured by the Madras Music Academy, and in 1958 became Vice-President of the Bharata Natyam Academy. Then, in 1959, she received the Sangeet Natak Akademi award for best dancer.

The citation ran as follows:

‘I crave your permission to make a reference to Smt. Mylapore Gouri Amma, a foremost exponent of Bharata Natyam style of dancing. I very much regret that owing to her ill health, it has not been possible for her to make the long journey from Madras to be present before you in person. Smt. Gouri Amma comes from a family of traditional dancers attached to the Kapileswari Temple, Mylapore. She had her training under the renowned Guru Nallur Muniswami Pillay. Smt. Gouri Amma had won acclaim as an unrivalled dancer 30 years ago. Her contribution to the revival of Bharata Natyam has been universally acknowledged. As a teacher, she has no equal in teaching abhinaya. She has trained a number of eminent dancers like Smt. Balasaraswati and Smt. Rukmini Devi. Even at this age of 65 Smt. Gouri Amma continues to teach abhinaya to aspiring students of dancing. The Madras Music Academy also honoured her in 1956. She is the Vice-president of the Bharatnatya Academy which conferred on her the title of Natya Kalanidhi in 1958. For her pre-eminence in Bharata Natyam and singular devotion and service to its cause, I pray, Sir, that you may be pleased to grant her recognition as Dancer of the Year in the field of Bharata Natyam, and to award to her a brocade Angavastram, a gold Mala and a Sanad in token of that recognition.’

Yet these activities and successes did not bring her prosperity. All the records indicate that she spent her last years in penury. One unnamed contributor to an article in Sruti Magazine states that she went blind, and that ‘her last years were troubled by irresponsible children’.

In an interview in The Hindu (April 3, 2009), Padma Subrahmanyam summed up the problems in this way:

‘The penury was caused by her drunkard son’s wasteful ways. Gauri Ammal was teaching at Kalakshetra and also teaching many reputed dancers outside the institution. But all her earnings were thrown away on liquor by her son. The grand-daughter, who was her only support from the family, did not have enough money to buy even a garland for Gauri Ammal’s body when she died. The last rites were performed by whatever was organized by Rukmini Devi.’

It is a blunt statement and seems cruel to the memory of Gauri Ammal, yet it also seems from a number of recollections that her son’s misbehaviour constituted a large part of the difficulties she endured in the last phases of her life. Her failing eyesight made teaching difficult and probably unrewarding too. Yet she went on working.

The colour photographs above appear in an article by Sunil Kothari, written shortly before Gauri Ammal’s death. The article is titled Mylapore Gowri Amma, and has the superscription: ‘The grand old lady of dance who, with the great Balasaraswati, is among the last of the devadasis who have enriched the traditional dance with their own inimitable contributions.’

The late Dr Kothari goes on to describe his first meeting with her in 1965, at Kalakshetra, where she was paid ‘a meagre salary.’ After describing a sanchari bhava improvisation by her (‘In a few seconds I saw the metamorphosis: an old woman turn into a young maiden recollecting her lover’s amorous advances’) he goes on to delineate her as ‘very old and of slight build, near-blind and frail.’ He relates how, meeting her again a month later ‘this poor old woman asked for some monetary assistance and requested me to get a job of a typist for her grandson! Next day I saw her waiting for a bus in a queue. That was the last I saw of her …’

And S. Rajam, speaking to Sruti Magazine in 2008 or 2009, concludes his reminiscence:

‘Gauri Ammal once came to All India Radio when her eyesight had dimmed and she could barely recognise me, but she patted me with great affection. She died a month later. My memories of Gauri Ammal are unforgettable – her majestic posture, her singing replete with suswaram, with bhava reigning supreme.’

In her earlier life, in 1932, when she was apparently destined for some late success on the proscenium stage, E. Krishna Iyer had written about her in his short collection of articles subsumed in 1933 under the title ‘Personalities in Present Day Music’:

‘Short of stature and fair of complexion, she has chiselled and expressive features of an attractive type and a good voice. She is further one of the very few who sing while showing abhinaya. She has a considerable variety of compositions and handles a number of padas in particular. Her gesturing is graceful and she observes a desirable proportion in the items of her dance. With good learning and long experience in the art she is also endowed with some general culture, and she displays her art with good mastery, skill, restraint and refinement. She has appreciable originality and manodharma and she is a good teacher in the art as well. Clever and masterly as she is in her rhythmic displays, she keeps them within desirable and enjoyable limits.’

This public success was never to be enjoyed by her, eclipsed as she was by the younger Balasaraswati, and by the gradual but rapid absorption of her art into the burgeoning success at Kalakshetra of Rukmini Devi and her students, most of whom were taught by Gauri in a final irony of historical fate.

END

‘